Gus Haenschen: The Radio Years

(Part 2)

.

The James A. Drake Interviews

Both Conrad Thibault and Annamary Dickey have commented on what an unusual team you and Frank Black were. They said that in every observable way, the two of you seem to have nothing in common except being pianists, arrangers, and conductors. Considering those differences, would enable the two of you to work together so well in radio?

I can see the differences they’re talking about, but they didn’t see how Frank and I interacted as business partners. What made it work, really, was Frank’s sense of humor—which was never on display in the studio—and the fact that we accepted our differences. Frank was extremely ambitious and ultimately it paid off for him: he became the Music Director for NBC. He had wanted to become a nationally known conductor of classical music. He knew that I had no such goal and that I was more interested in leading a balanced life, being not only married but the father of four kids. I can conduct most of the classical vocal and symphonic repertory, but as Frank knew, my real interest was in popular music.

There are almost no photos in which Frank Black is shown smiling, so it’s hard to detect any sense of humor from photographs of him.

Yes, but he had one. After he got a doctoral degree, he began insisting that he be billed and called “Dr. Frank Black.” He wanted an honorary degree because NBC always referred to Walter Damrosch as “Dr. Walter Damrosch.” He had graduated from Haverford [College], and his fame on radio netted him an honorary degree from there. I have two honorary doctorates but to me they’re nothing more than that—they’re honors, not degrees. And by the way, they come with a price tag on them because you’re expected to give money to the college.

.

Frank Black in the 1930s (left), and billed as “Dr. Frank Black”

on a World War II–era V Disc

.

Anyway, I really used to give it to him about this “Dr. Black” business. I would be in my office and would deliberately buzz our switchboard operator and say, “Please put me through to Dr. Black, and when he asks you who’s calling, tell him it’s Dr. Haenschen.” I used to razz him about it—never in front of a performer, of course—but I might say to him, “Jeez, Frank, this elbow of mine is really giving me trouble. Would you take a look at it and write a prescription for me?” He’d laugh because the razzing was a private thing between us.

Did you socialize together?

From time to time I would invite him to join Roxie and me and the Meltons on my boat. Frank was very fond of Jim Melton, and they worked together on several of Jim’s radio shows. He always wanted Frank as his conductor, and Frank liked working with Jim. So Jim and his wife Marjo [Marjorie], and sometimes just Jim and Frank and I, would cruise around Long Island on Sundays.

.

Haenschen aboard the yacht that Frank Munn and

James Melton helped him restore (1929)

.

I’ve seen photos of what you call your “boat” but those who were on it say it was a full-fledged yacht.

Technically, it was because 56 feet qualifies as a yacht. It was a mess when I bought it. It was built before World War One, and I had to redo it completely, which I enjoyed. I had two very able “helpers” in Jim Melton and Frank Munn, along with my son Richard and several of his friends. Jim Melton was a self-taught woodworker, and of course Frank had been a machinist, so I called on both of them to help me redo this yacht. Frank [Munn] and I did most of the machining in my shop at the house, and Jim did some of the finishing with marine-grade varnish. We’d work on it for three or four hours, and then we’d go in the house and Roxie would have our cook make whatever we wanted to eat.

That boat—or yacht—project, along with Jim’s collection of antique cars, had a lot to do with how he and Frank Munn became good friends. I couldn’t count how many gears, pulleys, and body panels I made in my shop for Jim’s growing collection of cars. Frank [Munn] would come over and he would work with me to sketch the parts and do the [specifications]. I did all the welding because I was pretty good with either gas or electric welding, which Frank hadn’t done a lot of. As Jim watched us making these special parts, he came to admire Frank more and more.

.

Antique-car enthusiast James Melton at the wheel, with members of the Denver Horseless Carriage Club (1950).

.

It was the same with the yacht. Frank [Munn] and I tore out the steam powerplant that the boat originally had, and I put in a twelve-cylinder gasoline engine that I had bored out, and I added a supercharger to maximize the horsepower. I put in a smaller gas engine to drive an AC generator so we could cook electrically and use electric lights, fans, and other appliances. I designed the new drive system, and Frank [Munn] and I made the transmission and machined the main drive shaft. I bought the propeller, and after working on so many of them when I was in the Navy, I knew how to balance it to get the most out of it.

What you call your “shop” is a little like what you call a “boat.” Your “shop” is a metal-working factory, and I think you’ll agree with that.

Well, all right, I’ll go along with “factory” because I can make just about anything there, I built it when I bought the acreage we live on in Norwalk [Connecticut], and as you probably noticed, all of the machines were originally belt-driven. I left all of the drive shafts in place, including the big Westinghouse motor that powered them, but then I adapted each piece of machinery to be run by a separate motor.

.

Haenschen as blacksmith (St. Louis Globe-Democrat,

April 23, 1939)

.

Your son Richard told me a story that I’m sure you’ll remember because it involved Frank Munn and the entryway to the cabin.

That was a hell of a thing. After I finished replacing the beams on the door frame of the cabin, Richard said to me, “Dad, that the space is too narrow for Frank to be able to go into the cabin.” That’s where the galley was, so we served our meals in the cabin. I couldn’t redo the entrance at that point, but I was so glad that Richard caught it because I special-ordered dining tables and large swivel chairs for the deck, and I had an electric awning that could cover the entire back of the deck so that I could always eat there with Frank. And on that subject, this will tell you about Jim Melton: he was just tall enough, about six-feet-three, that he had to watch his head when he went into the cabin. He used that as an excuse to eat on the deck with Frank and me.

.

(Left to right) Frank Munn, Lucy Monroe, and Gus Haenschen in a 1936 publicity shot for “The American Album of Familiar Music.” The program made its debut on NBC on October 11, 1931.

.

The sad fact about James Melton was that he died young, apparently from alcohol poisoning. Would you ever have predicted that his life would come to such a tragic end?

No, I didn’t see it coming but later on, when I had to deal with that in my own family, I learned more about alcoholism. Being hyperactive is often a factor in alcohol abuse, and it was in Jim Melton’s case. Anyone who knew Jim will tell you that he was hyperactive. He had to be doing something all the time, and it was very hard for him to relax. He couldn’t sit and have a leisurely conversation with you—he just wasn’t made that way.

.

Melton in the movies (1935)

.

When he would come over to our house, if the weather was nice, I would ask him to help our son Richard get better at football. Jim had played football in high school, and maybe at the University of Florida when he went there. So he would go outside and throw pass after pass to Richard and any friends of Richard who might be visiting that day. That would help him burn off some of his energy, and then he’d be calm for a while.

What was it about him that enabled him to get so many radio programs in prime time, with some of the biggest-name sponsors?

He had a way with people, especially people in power, but his eagerness almost always got in his way. For instance, he got to know Henry Ford II and his wife, and on a boat trip with them he talked Henry Ford into sponsoring a radio program for him. If he dealt with Ford the way he did with other sponsors, he’d get what he wanted and then would either want more—usually more money—or else he would stop socializing with them, or do something that sent a message that he had gotten what he wanted and that was that. I always thought that Henry Ford gave it just to put a stop to Jim badgering him about sponsoring a show for him. He could be very pushy that way—and after a while Ford pulled the plug on that show.

.

Frank Black (left), Dorothy Warenskjold (center), and James Melton during a “Ford Festival” broadcast in the early 1950s.

.

He even managed to get Irving Berlin to let him do an entire program about “Annie Get Your Gun” a week or so before the Broadway premiere—and Berlin was even part of the broadcast.

Yes, but there were reasons for that. At first, Berlin wasn’t as confident about “Annie Get Your Gun” as he was with the shows he had done when he was younger. As I remember it, it wasn’t until Dick Rogers told him how perfect the score was that Berlin felt that the show was going to be a hit. From then on, Berlin took every opportunity to promote the premiere. Melton’s show had good ratings at the time, so it was a good program for Berlin to promote “Annie.” And trust me, there wasn’t one word in Melton’s script, or one bar of music, that Berlin didn’t approve during the rehearsals.

If you look at the number of radio shows that [Melton] had, many of them didn’t last. He had to be the singer and the emcee, which was a big mistake because he minimized the announcer’s role. All he wanted the announcer to say was, “And now, here’s our star, James Melton,” then introduce the commercials, and say “Tune in next week” at the end of the show. He thought he was a great emcee but he was adequate at best. Frank Black often had to tell him that he was talking too fast when he was introducing whatever song he was going to sing next.

Were you surprised when he made the transition from popular music into the tenor ranks of the Metropolitan Opera?

The Met had always been his goal. I remember his debut in The Magic Flute very well, which was done in English in that production. Jim had very good guidance. [Wilfrid] Pelletier helped refine his phrasing in the French and Italian roles. [Melton] looked great onstage because he was tall, broad-shouldered, and very trim. He was especially good in Traviata, which I saw him in several times.

.

James Melton as Pinkerton in the Metropolitan Opera’s production of Madame Butterfly.

.

He had always wanted to sing Pinkerton in Butterfly, which he did at the Met, but it wasn’t his best role. The tessitura was a little too high for his voice. He was at his best when he could sing a B-flat. Now, he could sing the B-natural and even the high-C, [but] they didn’t have the “ping” that a tenor needs to have if he sings Pinkerton.

Did you stay in touch with him after it became apparent that he was becoming more and more dysfunctional?

No. I had to cut him off. I had already seen enough in my life, going back to my own father, of how destructive alcohol can be to a family. Jim called me at home at all hours of the night, drunk and wanting money from me, so finally I just cut him off completely. He died in some fleabag hotel, drunk and alone. Roxie and I stayed close to Marjo and their daughter Margo, and we felt helpless because of the way he left them. He abandoned them. One thing that struck me was that his alcoholism never affected his voice. He made some low-budget recordings a year or so before he died, and he sounded just like he did twenty years earlier.

.

(Top) In 1948, Melton moved to Florida with his collection of antique cars and opened Autorama, a tourist attraction that closed following his death in 1961. (Bottom) Melton on a cut-rate Tops LP in the 1950s, an ignominious ending for a one-time Victor Red Seal star.

His style seems to have changed, though. After he left The Revelers, he sounded like an Irish tenor, but after the war he sounded more “mainstream” for want of a better word.

He was trying to sound like [John] McCormack at first, almost to the point that he sounded like an impersonator. He stopped that after he had a bad experience with McCormack.

Did you know John McCormack?

In a funny way, yes. We had the same dentist, a very well-known oral surgeon in Manhattan. I was surprised that McCormack let him do this—although it’s probably because McCormack didn’t have to pay him—but the dentist was very proud of a special set of dentures he had designed for McCormack to use in his concerts.

These dentures were very lightweight, and the upper plate had no artificial “roof”—it was just a U-shaped denture that left the roof of the mouth exposed. They were cosmetic, not for eating, and the dentist was so proud of them that he had a set in a display case in his waiting room, with a thank-you note that McCormack had signed.

Anyway, I was introduced to McCormack several times but I can’t say that I knew him. I had heard him in concert when I was in college, and maybe four or five times later on. There was nobody like him on a concert platform.

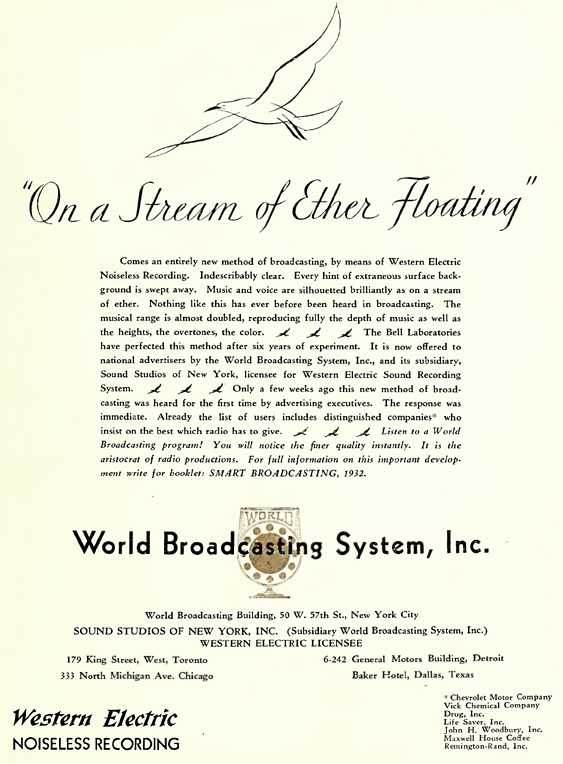

Returning to you and “Dr. Black,” how did the two of you and your other partners go about developing the World Broadcasting Company?

For the first three years, World Broadcasting was all-consuming. We had to hire lots of musicians, arrangers, and engineers for Sound Studios, which we built and where we did the recording sessions. The small independent stations were clamoring for more and more recordings, so we had to run Sound Studios almost like a factory. We started recording at 10:00 a.m., Monday through Friday, and took a half-hour break at 2:00 p.m., which usually lasted about forty-five minutes by the time we were recording again. We would record till 6:00 p.m., and that would be a typical daytime session.

.

(Top) World Broadcasting / Sound Studios’ 1931 announcement of Western Electric Noiseless Transcriptions, embodying vinylite pressings and other improvements. (Bottom left) A standard World Broadcasting transcription label, mid-1930s; (bottom right) Sound Studios’ special “Superman” transcription label, 1940s.

.

Since most of the guys we hired to play for us were in bands and had nighttime gigs, we started holding a midnight session that would last till 3:00 a.m. We did those on Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays. We always had the best catered food—a really impressive buffet—at every daytime session and at those midnight ones as well. But the food, good as it was, wasn’t what enabled us to get anybody we wanted in our sessions. The key was that we paid everyone 25% over scale for each session. This was during the worst of the Depression, so a really driven guy like Artie Shaw would do a morning and afternoon session before playing an evening gig with whatever band he was playing in.

Aside from you, Ben Selvin, and Frank Black, who were the conductors you retained for the World Broadcasting sessions?

We used everybody we could get—Vic Arden, Ed Smalle, Ben Bernie, Jack Denny, Jerry Freedman, Harold Stanford, Don Donnie, Gene Ormandy, Don Voorhees, and of course Ben [Selvin]. For the first year, Ben, Vic [Arden] and Frank [Black] and I conducted the daytime sessions.

Were Abe Lyman and Gus Arnheim with you at World Broadcasting?

No, they were in California by then. But we did give some aspiring conductors their starts as well. We may have been the first to have André Kostelanetz conduct, and also Edwin McArthur. Both were pianists and arrangers for us.

I’d like to make it a matter of record that when you and Eugene Ormandy happened to see each other here at Philharmonic Hall when he was with a group, he made a point of introducing you to each of his friends and said you had given him his start, but as a dance-band leader.

It’s true, and we also used Gene as an arranger.

We’ll also make it a matter of record that you said to him, “Good to see you, Gene, and if this symphonic gig doesn’t work out, I think I can get you some dance-band work.” From your files, it appears that every future leader of one of the big bands—Artie Shaw, Benny Goodman, the Dorsey brothers, Harry James, Glenn Miller—all played in World Broadcasting sessions. So did Jan Peerce, among the vocalists you used a lot at World Broadcasting.

He wasn’t “Jan Peerce” back then. He was “Pinky Pearl” when we first hired him. He was exactly the kind of performer we were always looking for. He was a violinist and a singer, and he could play “straight” violin as well as jazz violin. As he told you, his inspiration was Joe Venuti, the greatest of them all. Jan wasn’t the improviser that Joe Venuti was, but he was very, very good. As a singer, he could do songs from operettas like The Student Prince, Rose Marie, and the others, but he could also sing like a crooner. We used him under lots of different names.

.

Jan Peerce (left) and Ben Selvin

I know that you wanted to get his brother-in-law, Richard Tucker, for some World Broadcasting sessions, but I take it that Peerce blocked it. Is that right?

I had no idea that there was such animosity between them, but I found out when I mentioned to Jan that I’d like to use Tucker for some studio sessions. Tucker was doing the “Chicago Theatre of the Air” every week, and he was building a name for himself through those broadcasts.

Was Peerce already at the Met at that time?

Yes, and he was doing very, very well. He was managed by [Sol] Hurok, and he was one of Hurok’s personal favorites. I don’t know what [Peerce’s] problem with Tucker was, but Jan blew his top when I brought up his name, and it really put me off. I knew several of the guys who helped Jan when he was coming up, and I couldn’t believe that he wouldn’t let anybody help his brother-in-law. But fate has a way of taking care of things, and Tucker is the “king of the Met” and Jan isn’t there anymore. He did well on Broadway, though, in “Fiddler on the Roof.”

I was able to help Tucker after all, and I know that Jan found out about it. I had heard from John Charles Thomas that he was having trouble getting a summer replacement on “The Westinghouse Hour,” so I suggested Tucker to John, and Tucker ended up being his summer replacement.

.

(Left to right) Conductor Emil Cooper, Richard Tucker, Paul Althouse (Tucker’s teacher), Jan Peerce, and Edward Johnson after Tucker’s Metropolitan Opera debut (January 25, 1945)

.

Who were some of the other singers who made World Broadcasting transcriptions?

Most of the singers we had at Brunswick—Elizabeth Lennox, Virginia Rea, Frank Luther, Billy Hillpot, Billy Mann, Morton Downey, Scrappy Lambert, and of course Frank Munn—worked for us at World Broadcasting. We also used Irving Kaufman, and sometimes his brother Jack, when they were available.

.

A 1939 ad for World Broadcasting’s Library Service. Along with Associated, NBC, and others, World offered a subscription service that provided radio stations with long-playing, multi-selection transcriptions by nationally known artists—some of whom appeared under aliases because they held exclusive contracts with the commercial labels.

.

Vaughn Monroe shows up in some of the World Broadcasting sessions. Was he one of your singers?

No, Vaughn played trumpet with us, although he did sing in trios, quartets and such. He was like Jim Melton, who doubled as a sax player for us while he was in The Revelers.

Let’s stay with the saxophone, because just about every sax player seems except Carmen Lombardo played in those Sound Studios sessions. I’m assuming that you know all of the Lombardos, am I right?

Oh, sure. I had tried to get them during my last year at Brunswick. Ben [Selvin] signed them to Columbia, and he really helped them. You know why Guy is the leader, don’t you? It’s because he’s the only one of the brothers who wasn’t a good musician. Supposedly, he played the violin but he wasn’t any good, yet he was nice-looking and he had a good speaking voice so he became the leader. Carmen [Lombardo] is the one who came up with the Lombardo sound, and he was always the behind-the-scenes leader of the band. Guy’s real passion is boating. I think he’s still competing in big-league powerboat racing.

Your friend Tony Randall is on a television campaign to bring back Carmen as the band’s vocalist. Do you think that will happen?

As long as Carmen doesn’t have to be interviewed, he might do it for Tony because they’re good friends. Anybody who knows Carmen will tell you that he’s nothing like the caricature of him. Of the brothers, Carmen is the one who’s known for liking the ladies, and they like him. He also has a great sense of humor. So do Victor and Lebert and Guy. Their philosophy has always been that the more they get made fun of, the more attention the band gets, and they laugh all the way to the bank. But make no mistake about it, Carmen is the leader and the main arranger, and always has been. The precision of that sax section is Carmen’s doing. They play so tightly that even their vibratos are in synch.

One of the sax players you used in many World Broadcasting sessions was Fred MacMurray, whom I never knew was a musician.

Fred was a very good tenor-sax man. He was with George Olsen’s band, but he did as much freelance work as he could get. He did some singing with George, as did Fran Frey, another of George’s sax men. We used Fran in some of our sessions, but not as much as Fred. Later on, Sid Caesar did some work for us [at World broadcasting] and he played in one of my radio bands.

.

Future comedians Fred MacMurray (top left) and Sid Caesar (top right) did session work for Haenschen at World Broadcasting, as saxophone players. Below, Caesar with the Coast Guards’ Brooklyn Barracks Band (center, standing with clarinet).

.

The comedian Sid Caesar?

Yes, that Sid Caesar—a hell of a good tenor sax man. He had been playing sax in the Catskills while he was doing comedies and impersonations there. He was in the Coast Guard during the war, but he was stationed in New York and he played for us as often as he could.

How would the great sax players of what’s now called the “Big Band Era” compare with such greats as Rudy Wiedoeft and Benny Krueger, whom you recorded at Brunswick?

If Rudy or Benny were still here, they would tell you that the Brown brothers, or the Six Brown Brothers as they were billed, were every bit as good as they were. Tom Brown led the band, which was a saxophone quintet at first—two alto saxes plus a bass, baritone and tenor sax. The other brothers—Bill, Percy, Alec, Fred, and Vernie—played the bass, baritone, and tenor saxes. For me, though, Rudy Wiedoeft was the best sax player I ever worked with, but I also knew him better than the others.

Rudy, Benny [ Krueger] and all of the top-notch sax players back then had what reed players call a “diaphragmatic vibrato.” Some of the later sax players used jaw muscles for the vibrato. Tex Beneke could do both, but a lot of the time he used the “jaw vibrato.” If you watch film of Tex playing, and then watch Rudy Wiedoeft, you won’t see any movement of the jaw in Rudy’s playing. That’s the difference between a vibrato that comes from the diaphragm, like an opera singer has, and a “jaw vibrato.” Sax players can get away with a jaw vibrato, but a clarinetist can’t because the embouchure, or the way the lips are placed on the mouthpiece, is much tighter than on a saxophone.

.

Haenschen plays Detroit (May 2, 1940)

.

You had another reed player who has done very well for himself: Mitch Miller.

Mitch was one of the best oboists in the business—I can’t think of any other oboist who could match him.

He and Percy Faith, with John Hammond, remade Columbia Records. Was Percy Faith in any of the Sound Studios sessions?

No, he wasn’t in New York in those days. He’s Canadian, and the Lombardos helped him get work in Chicago as an arranger and conductor. He worked for Jack Kapp at Decca, and later on he conducted “The Contented Hour.”

That was one of your radio shows, wasn’t it?

Yes, and most of the band had also done World Broadcasting sessions with me. Both of the Dorseys, Glenn Miller, and I think Artie [Shaw] were in “The Contented Hour” band during my time with the show.

.

Do you remember if Benny Goodman was in that band? Was he a “doubler” like Shaw was?

Benny Goodman is one of the finest clarinetists I’ve heard, but he was also one of the worst sax players I ever heard. What amazed me was that he couldn’t tell the difference. He couldn’t hear how bad his tone on the sax was. Now, Artie, on the other hand, was every bit as fine a sax player as he was a clarinetist. The same with Jimmy Dorsey, who was equally good on both instruments. I would put Jimmy Dorsey and Artie Shaw up against any sax players, even Rudy Wiedoeft, and they would hold their own.

Do you recall the incident that Artie Shaw talked about, the incident between Benny Goodman and him during a rehearsal that you were conducting?

That was for one of our radio shows, not World Broadcasting—but yes, I remembered it when Artie brought it up. The two of them were side-by-side in the sax section, and Artie always played the lead and Benny the second part. All I remember is that when we ran through a passage a second time, the lead sax was under pitch and had this buzzy sort of tone. I stopped and said, “Who played that?” Benny jumped up and said, “I did!”

I remember questioning Artie, and him saying that Benny had asked him to play the lead for change. All I said was, “Don’t do that again” and went on with the rehearsal. If I didn’t know Benny, I’d think he still holds that against me. But I know him, and he’s just plain dense. There are so many stories about what an oddball he is, and most of them are true.

Did you have black players in the World Broadcasting sessions, along with white players?

Definitely. The sax players, for instance, included Johnny Hodges and Benny Carter, who were terrific players, and they were good clarinetists too.

.

Benny Carter (top) and Johnny Hodges.

.

Was there any resistance from white players?

Not unless they wanted to get fired. Seriously, though, every player we had—and I can’t think of a single exception—were in awe of Louis Armstrong, Sidney Bechet, and Duke Ellington because they set the standards for jazz. I had recorded Duke at Brunswick, but that was before he developed his own style. That’s just a short list if you think of the pianists of that era—James P. Johnson in particular, and Fats Waller, who was a classical organist in addition to a terrific pianist.

A lot of the small stations in the South and the Midwest wanted gospel songs, so we brought in groups from the Tuskegee and the Fisk University singers. Often we used members of the choirs of the big congregations in Harlem.

Especially in the Midwest, there must have been a demand for “hillbilly” music. Did you import any performers like the ones Jack Kapp brought to you at Brunswick?

No. When Jack [Kapp] was recording those backwoods players, he was using field-recording equipment most of the time. We never did field recordings. All of our sessions were done at Sound Studios.

.

1937

.

You had some of the finest brass players ever—and yet there was one whom neither you nor Ben Selvin have any memory of: Bix Beiderbecke. When I interviewed both of you and brought up that name, Mr. Selvin said, “Oh, he was great,” or words to that effect, and then he said, “Didn’t you think so, Gus?” Your reply, which I transcribed, was, “Benny, I don’t know how many people have asked me about him, and to tell you the truth I never heard of him.” That prompted Mr. Selvin to say, “I thought I was the only one! I’ve been shown pictures of this guy, and I swear he was never in any band that I recorded!”

But that’s the truth. The stories I’ve heard are that even Louis Armstrong considered him an equal. I find that very hard to believe, but Artie [Shaw] said he roomed with [Beiderbecke] and that he was in several World Broadcasting sessions. Jim Lytell remembered him very well, too. All I can say is that if the guy was in any band that I directed, he must have sneaked in, played, and sneaked out.

It’s more remarkable that Ben Selvin had no memory of Beiderbecke because it was Ben Selvin who got Paul Whiteman to sign with Columbia, and Bix Beiderbecke was in the Whiteman band at that time. Is it possible that both of you didn’t know all the players you used at World Broadcasting and on some of your radio shows?

Well, if you want to be literal about it, it’s possible but very, very unlikely, especially at World Broadcasting. We always had five or six players on call for every instrument in those sessions. We had to have that many because of the number of recording sessions day after day.

Now, it is possible that a player we didn’t use very often—and keep in mind that we hired players based on recommendations from the other players on our payroll—it’s possible that some player might not stand out because of the type of music we were recording. We weren’t recording jazz, we were recording pop instrumental music.

To be honest about it, most of the players who were “regulars,” and I’ll use the Dorseys as an example, played in our sessions for the money because that’s all that was in it for them. I’m sure Tommy Dorsey couldn’t stand many of our arrangements, but it was steady work and very well-paying work. Payday was every Friday, and if a player needed an advance, we’d give it to them and deduct it at the end of the week.

You have to remember that these guys were known to each other, but not to the public. In 1932, Artie Shaw could walk down any street in broad daylight and nobody would know he was. Ten years later, he would be hounded everywhere he went. But during the worst of the Depression, all of these players needed the money, and we were paying more than they were getting anywhere else. Our sessions went like clockwork, so they were in and out, and maybe back again for a second or even a third session. World Broadcasting was a business, and we ran it like one. We were the Ford Motor Company of the radio business.

— J. A. D.

Text © 2019 by James A. Drake. All rights are reserved.

Discover more from American Sound-Recording History from Mainspring Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.