Gus Haenschen: The Brunswick Years (Part 3)

.

Charlie Chapli

Charlie Chapli

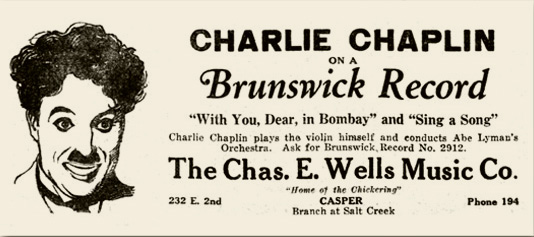

It was in Los Angeles that you recorded Charlie Chaplin with Abe Lyman’s orchestra, am I right?

Yes, Abe Lyman’s band with Charlie listed on the records—we did two sides, as I recall—as “guest conductor.”

Although it’s known today that Chaplin wrote the scores for all of his films, I doubt that it was known then. How did you come to record him as a “guest conductor”? Did you know him at that time?

Not personally, no, but of course I was a fan of his movies. Charlie contacted me through Abe Lyman. That’s how those records came about. Charlie wrote songs all the time, and he wanted to have about a dozen of them recorded. When Abe [Lyman] told me that Charlie was interested in having his songs recorded, I told Percy Deutsch about it and he said to pay Charlie whatever he wanted because having the name Charlie Chaplin on Brunswick records would be one of our “exclusives” and would sell a lot of records for us.

Did you negotiate a contract with Chaplin?

He didn’t want a contract. Money wasn’t a factor because he was already one of the wealthiest movie stars and was also one of the “big four” [Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, David Wark Griffith, and Chaplin] who founded United Artists. What he wanted to do was to have his songs recorded, and he also wanted to conduct them and then play a violin solo in some of the recordings. So basically, he agreed to try out some recordings with us, and if there was a demand for more, he would talk to us about royalties and such.

.

Publicity shots from the May 1923 session (the exact date has not survived in the Brunswick files). In the top photo, Gus Kahn is seated at the piano, with (left to right) Haenschen, Chaplin, and Abe Lyman.

What do you remember about making the recordings?

Charlie was so excited that he wanted me to show him everything about the recording process. I took Frank Hofbauer to Los Angeles with me because he was our “expert,” and he would design the permanent studios we intended to build there and would also do the recordings we made in the temporary studio we used. So I spent almost a full day with Charlie, showing him how the recording process worked.

Then Abe [Lyman] and Gus Kahn and I spent part of an afternoon with Charlie. Gus worked directly with Charlie to write the arrangements for the first two songs we were going to record. Everything was going well until Charlie played the violin for us. He was self-taught, and he played left-handed so he had his violin strung the opposite of a standard violin. His playing was so amateurish that there was no way we were going to allow him to play any solo passages on a Brunswick recording.

.

Although Chaplin’s record was widely advertised, it was not a big seller for Brunswick. Some dealer ads, like the lower example, claimed that Chaplin played violin on the record, which Haenschen recalled was not the case.

.

Because Abe [Lyman] knew him well, I left it to Abe to have to tell Charlie that he couldn’t play on an actual recording. But we agreed that Charlie should really conduct the recording session, which he did—not with a baton or with his hands, but with his violin bow. The day we made the first two recordings, he brought a camera crew with him. They set up all sorts of lights around the studio, and the crew filmed him and us during the whole session. It was a fun experience, and afterward Charlie treated all of us to a dinner at his studios.

Unfortunately, the “try out” that all of us had envisioned didn’t sell any records. Looking back, I can see why. At that time [1923], movies were silent and Charlie was seen but never heard. And as you said, very few people knew—or cared—that he wrote the scores for his films. Movie audiences weren’t listening to his music, they were watching him on the screen. In the silent-movie days, no one associated Charlie Chaplin with sound recordings, so the fact that he was listed on two Brunswick sides as the “guest conductor” of the Abe Lyman band didn’t mean anything from a promotion standpoint.

But that wasn’t the end of it—in fact, in some ways it was just the beginning. Charlie wanted to record all of the songs he had mentioned, about a dozen of them, and he was relentless about it. He sent me telegrams day and night, he nearly drove Abe Lyman crazy, and then he sent me scores that he had had someone make of all the songs. I had to find more ways of saying no than I had ever known until then. Finally, he stopped “campaigning” and went back to working day and night on his movies.

But about the time [Chaplin] had given up on us, Rudolph Valentino contacted us and wanted to make records too. [1] Everyone knew that Valentino was a splendid dancer, and of course he was the biggest name in movies in the mid-1920s. He told Bill Brophy and me that he had studied voice in Italy, and would sing on our recordings. We had no reason to dispute what he said, so we agreed to record him in New York. We did—and the two songs he sang on those recordings were the worst ever made by Brunswick or any other company.

What did he sing? Was it an opera aria or a song?

I can only remember one of them, the “Kashmiri Song,” which he sang in English. He spoke English fluently, by the way. [John] McCormack and so many other real singers had recorded it, and it’s a good song so we figured Valentino could sing it credibly. Of course, we also figured that having his name on a Brunswick label, and introducing him to the public as not just the great lover, the movie star, but also as a singer would be another exclusive for us.

Well, the recording was an absolute disaster! If he had ever had a voice lesson, it didn’t “take” because his timbre was awful, and his intonation was even worse. He was either under-pitch or above-pitch throughout most of the recording. The other one we made with him was a popular Spanish song [”El Relicario”] that he sang in Spanish—and it was even worse than the “Kashmiri Song.” Both of the test pressings were so bad that we would never have released them. If we did, we would have been the laughingstock of the industry.

Was Valentino as relentless as Chaplin was about pressuring you to release them?

Percy Deutsch and two other executives, Ed Bensinger and Bill Brophy, kept putting off Valentino by telling him that Brunswick would prefer to wait to release his record in connection with his next biggest film. They kept putting him off for almost two years, and then—and this sounds awful—he solved Brunswick’s problem by dying in 1926.

.

Brunswick did not release the Valentino recordings, although a catalog number to them was assigned following his death. In 1930 it dubbed the recordings, with spoken introductions, for a special release by the obscure Celebrities Recording Company.

Those recordings were released after his death. Did Brunswick release them after all?

No, no. Some record company—it wasn’t Brunswick—put out a sort of “memorial record” with a pompous introduction explaining that these two songs were the only time that the voice of Valentino was ever recorded. I don’t know how those test recordings got released. Maybe somebody got the test pressings from his estate, I don’t know. I had left Brunswick by then, so I don’t know if the company got an injunction or sued whoever it was that released them. [2]

In your files there are letters between you and Oliver Hardy about making records for Brunswick. Do you recall your dealings with Hardy?

Yes, and they were very pleasant. I met him when I went to Los Angeles to set up the temporary studio, the one where we recorded Chaplin. You may know this, but everybody who knew Hardy called him “Babe,” not “Ollie” or “Oliver.” He had been a singer before he got into [motion] pictures, and he had a very pleasant tenor voice. The problem was that he and Stan Laurel were making silent pictures, so no one knew that Hardy could sing. But he could really sing—and he did when he and Laurel made sound pictures. He was also a hell of a golfer, by the way. Like Bing [Crosby], he was almost a par golfer.

Your files also contain some correspondence with two other film stars, Ramon Navarro and John Boles, who wanted to make records with Brunswick. Do you recall dealing with them?

With Navarro, yes, in Los Angeles. He was a competent “salon pianist,” but as with Hardy, no one knew that he had any musical ability. The same with John Boles. Although I did meet with him and he was a very nice guy, [Boles] was another case of a silent movie star who could sing credibly but no one knew it, so there was no point in having him make records for us. As a movie star, he was nowhere near Valentino, but [Boles] could sing—his voice was a light baritone, or maybe a tenor with a limited top [range] and a fast vibrato—but he made several successful sound films later on. [3]

Among the vocalists you recorded at Brunswick, there are two tenors I’d like to ask you about. The first is Frank Munn, whom you discovered. How did that come about?

Being a machinist myself, I had a lot of friends who were master machinists. I kept hearing about this rotund machinist who had this beautiful tenor voice, but had lost part of his index finger in an accident and was now driving trucks. After a while I found out his name, so I looked him up in the phone book and found that he was living in a little apartment in the Bronx.

Frank was a very shy man, and when I introduced myself to him and told him that I heard he was a singer, he seemed kind of lost for words. I could see how reticent he was, so I asked him where he liked to eat, and then told him I want to treat him to lunch on a Sunday. He was still very reticent when we got together, and I think it was because he had found out that I was with a major record company. I actually had to convince him to audition for us—that’s how shy he was.

Frank was what used to be called a “Mister Five-by-Five.” He was about 5’ 5” and he weighed close to 300 pounds, so he was almost as round as he was tall. He had two suits and two dress shirts that had to be custom-tailored for him due to his size. He was single back then, but later he married a wonderful woman, Ruth, who was the dream of his life. She took wonderful care of him, and they were such a great couple. Being so overweight, he was extremely sensitive about it, but in her eyes he was as handsome as a movie star—and she loved to hear him sing.

.

Frank Munn, from Radio Revue for February 1930

.

We [Brunswick] were already doing the “Brunswick Hour” when I met Frank, and we had ironed out the problems with electrical recording by then. His voice recorded so well that it amazed all of us. I didn’t know it at the time, but he had made some personal recordings and had even done a trial recording for Edison. [4] But those were acoustic recordings, and like Nick Lucas, Frank didn’t have the kind of voice that recorded well acoustically. [5] But on electrical recordings and on radio, Frank’s voice was just beautiful.

Because of his obesity, his boyish face, very light skin, and the timbre of his speaking voice—which was exactly like his singing voice—and his shyness, you wouldn’t take Frank for being a strong man. Well, one day in the studio we found out just how strong he was. It was a hot summer day, and we were re-doing the studios—we had three of them, and one studio was still equipped with one of the very heavy acoustic recorders that Frank Hofbauer had designed. We needed to get it out of there, and four workmen were hired to remove it.

Well, only two showed up—and we waited and waited for the other two, but they never showed. We were on a tight schedule and weren’t doing any recording while the studios were all being redone, so I was infuriated about these two workmen not showing up. It was very hot—this was in July, I think—and tempers were getting short. Frank was there to rehearse in another room with several men from our Brunswick Male Chorus. He was always punctual, and had arrived early for this rehearsal.

When he saw what was going on, he said to me, “I can help with this,” and he picked up one side of this very heavy machine as if it didn’t weigh ten pounds! The other two workmen were struggling to keep it off the ground, but Frank was not only lifting and moving what it would have taken two men to do, he was also telling the other two to move this way and that way until that machine was out of the room.

Word got around that Frank was super-strong, and when some of the guys would tell him they had heard about it, Frank reacted very modestly but you could tell it meant something to him. From then on, we made bets about what he could lift. One bet that I especially remember was whether he could lift the rear end of a Ford sedan high enough that the rear tires would not be touching the pavement. One of our [Brunswick] fellows had a four-door Model T with a back bumper on it, and I watched Frank Munn put on a pair of leather gloves and lift the entire rear end of that Ford until the tires were almost two inches above the pavement!

Frank Munn’s voice has a very sweet quality, for want of a better word, on his recordings. Had he studied voice formally?

Frank never had any lessons as far as I know. His voice was just “natural.” It wasn’t large, nor did it have much of a range. When I wrote arrangements for Frank’s recordings, I tried not to have him sing above an A-flat because he didn’t have much of a top. But the timbre of his voice gave the impression that he was singing higher. To me, the best things about his singing were his intonation, his phrasing, which was always on the beat, and his natural diction—no rolling of the Rs and that sort of thing.

Frank was ideal for recording and for radio because he was never seen by an audience, so he didn’t have to worry about his obesity. He didn’t like having photos taken, but we used the best professionals and they lighted him in ways that emphasized his dark hair and his eyes and his smile, not his body. When he had to pose for longer shots, he would stand behind a piano so that the photo would be of his upper body.

.

A hand-colored photo of Virginia Rea and Frank Munn, with Haenschen at the piano (1928)

.

I remember a photo session with Frank, Virginia Rea and me—I was seated at the piano, and they were in formal dress standing in front of microphones—which became the cover picture for one of the monthly radio magazines that were popular back then. The photo was hand-colored, and the background was quite dark. Frank positioned himself slightly behind Virginia [Rea], and his black tuxedo blended into the dark background. He was very fond of that magazine-cover photo.

Another tenor you had under contract at Brunswick was Theo Karle. What do you recall of him?

We made a lot of recordings with Theo Karle. If I had to liken him to another tenor, at least on recordings, I’d say that he was Brunswick’s Giovanni Martinelli. He had an unusual timbre that on [acoustical] recordings sounded somewhat like Martinelli’s. He recorded tenor arias from Italian and French operas but did them in English, and also sang oratorio selections for us. We recorded him singing operetta selections—he was the main tenor in our Brunswick Light Opera Company—and he also recorded several Irish ballads. His wasn’t a great voice, but it recorded well and he was very easy to work with.

.

Allen McQuhae (left) and Theo Karle

.

Another tenor I want to ask you about it your Irish tenor, Allen McQuhae. Was he Brunswick’s John McCormack?

If he thought he was, someone should have disabused him of it. He was an “Irish tenor” only in the sense that he was born there, and sang some of McCormack’s repertoire. Most of his earlier [career] was spent in the Midwest—Cleveland, Detroit, Cincinnati—singing with their symphonies. At that time, he was singing French and Italian arias, and some oratorio pieces. I think he had also done some singing in Canada, which is where he emigrated after leaving Ireland.

Personally, I never thought much of his voice or of his singing. His timbre wasn’t that distinctive or attractive, and the dynamic he preferred the most was forte. There was very little subtlety in his singing, and nothing memorable about it either. We used him more as a pop singer than an “Irish tenor” at Brunswick. He had made some recordings for Edison, and they weren’t very good, so to be honest about it, I wasn’t in favor of giving him a contract. I wanted Joe White, but he was already under contract to Victor so I couldn’t get him.

You’re referring to Joseph White, the “Silver-Masked Tenor”?

That’s right, Joe White of the [B. F.] Goodrich Silvertown Cord Orchestra. To me, Joe sounded the most like McCormack of any of the tenors I had heard. He and I became very good friends, and I would love to have had him under contract at Brunswick. But he was already with Victor and was doing very well as Goodrich’s star tenor. He had sung on radio before Victor put him under contract, and he had also sung in Europe if my memory is right. But it was as the Silver-Masked Tenor at Victor that he was best known on radio and recordings.

Joe has a son who sang under the name “Bobby White” on several radio shows, particularly “Coast to Coast on a Bus” with my friend Milton Cross [as announcer]. Bobby had an unusually beautiful voice as a boy, and Joe oversaw his training and taught him all of his [the father’s] songs. Joe was still singing, but then he had an accident and broke one of his legs. As I recall, the break wouldn’t heal, and that leg had to be amputated. Through all of that, Joe made certain that Bobby would make the transition into adulthood as a tenor, and he surely did a wonderful job. Today, Bobby—or Robert—White is a nationally known concert tenor and gives recitals all over the world.

Am I correct that you also had Ted Fiorito under contract at Brunswick?

Well, at that time Ted was the pianist of the Oriole Orchestra, which he led with a violinist, Dan Russo. They made a good number of recordings for us as the Orioles [sic; Oriole Orchestra or Oriole Terrace Orchestra]. Several of their recordings were done in Chicago because their orchestra had a long engagement at the Edgewater Beach Hotel there.

One of the most unusual groups you recorded at Brunswick was the Mound City Blue Blowers, a group which became nationally known in its own right. How did they come to your attention?

Through Al Jolson. The credit for the Mound City Blue Blowers goes to Jolson. We were recording him at the Statler [Hotel] in Chicago, and these three young guys had been bugging Jolson to give them a hearing. Finally he got tired of it, so he passed the buck to me and got me to give them an audition. I think we made a couple of test pressings, unwillingly, and we sort of tossed off the whole thing by telling them that we’d have to issue their records on a trial basis, and if they sold anything we might talk to them later.

.

(Top) The Mound City Blue Blowers c. early 1925, comprising (left to right) Dick Slevin, Jack Bland, Eddie Lang, and Red McKenzie. The group originally was a trio, minus Lang, although Brunswick’s ad for their first record pictured a quartet.

.

The one who put together the group—it [initially] was a trio—was Red McKenzie, who was from St. Louis. Red went on to have a very fine career, but when we auditioned the Blue Blowers I wouldn’t have given him or the other two a snowball’s chance in hell. All Red did was play a comb with tissue paper wrapped around it.

Yet here was something different about the sound of the group, so it gave me something to work with. One of the three played banjo—Bland, Jack Bland, was his name—but he was no Harry Reser, so I backed him with Eddie Lang on guitar and I also put Frank Trumbauer in the next set of Blue Blowers recordings we made. Well those records sold, and sold, and then sold some more. We couldn’t believe it because these young guys were nothing more than a “kitchen band,” what with jugs and all of that. [6] But here they were, selling a lot of records for us.

Returning to classical Brunswick artists, and in particular violinists, you spoke about Elias Breeskin and Max Rosen earlier. Let me ask you about other violinists you recorded at Brunswick: Fredric Fradkin, William Kroll, Bronislaw Huberman and Mishel Piastro.

Kroll wasn’t a soloist—not for Brunswick, I mean. He was the violinist in a trio, the Elschuco Trio, with a pianist [Aurelio Giorni] and Willem Willeke, who was a superb cellist. Max Rosen, as I said, was [Brunswick’s] Fritz Kreisler. The others were not in his class, although Huberman was a close second to Rosen. Huberman had studied with Joachim, and had been a sort of prodigy when he came to this country. He had played all over Europe by then. We recorded him in the standard repertoire that Victor had in its catalogs.

Piastro and Fradkin were competent violinists, but they didn’t sell a lot of records and didn’t have the following, the careers, that Rosen and Huberman had. Breeskin was a fine violinist, and we got a lot of mileage out of having him at Brunswick because he was the violinist Caruso chose as an assisting artist for his U.S. concert tours in World War One. By the way, another [violinist] Caruso had as an assisting artist in some of his concerts was Xavier Cugat. Back then, he was “Francis X. Cugat.”

.

Haenschen recalled getting “a lot of mileage out of having [Breeskin] at Brunswick” because of his association with Caruso.

.

Among the legendary pianists Brunswick had under contract were Josef Hofmann, Leopold Godowsky and Elly Ney. First, let me ask you about Josef Hofmann. It was rumored that because his reach [i.e., the span of his hands] was somewhat short compared to, say, Rachmaninoff, that he used a special piano that had slightly narrower keys than a standard concert grand.

That was much later, not when he was with us. It would have been quite a trick to have one of those special Steinways hauled from his studio onto the top floor of the Brunswick building. No, when he recorded for us, he used the same grand pianos that the others you mentioned used. We had four grands, all of them seven-feet models. Two were Steinways and the other two were Knabe grands.

Hofmann always played one of the Steinways, but it had a standard keyboard. It’s true that his reach was short compared to Godowsky’s, but even Godowsky said that Hofmann had the finest technique of all the concert pianists of that time. Hofmann had very strong hands, incidentally, and he could get more volume out of any of our pianos than even Godowsky could. That’s saying something because Leopold Godowsky was one of the greatest pianists ever. One thing about Josef Hofmann just came to my mind: he had a special chair built for him—he had a number of them, actually—and he would only record in that special chair.

Do you mean a “chair” rather than a piano stool or bench—that is, a seat with a back on it?

Yes, an actual chair with a back on it. The height of the back was maybe twelve inches, not much more than that, and it was angled slightly forward. There was something about the height and the angle of the back that kept him in a position that was ideal for his playing. That’s what he used in his concerts, and he always used it in our recording sessions. He was a wonderful guy, always a lot of fun to work with.

Another point about his style that always struck me when I watched him recording for us: his fingers were never more an inch above the keys, and his wrists were always on the same plane as the tops of the keys. He didn’t go in for showy stuff—no bringing his arms up to his shoulders and then down to the keys, or any of that Liberace fluff.

.

Elly Ney (left) and Josef Hofmann (right, in the Columbia studio)

(G. G. Bain Collection, Library of Congress)

..

And Elly Ney?

Elly was a great pianist, and one of the few women pianists who had very successful careers at that time. She was German but spoke English well. She was a bit on the flamboyant side and had a really captivating personality. There was a very famous pianist in Vienna, [Theodor] Leschetizky, who taught a lot of famous concert pianists. Elly’s concert promoters always highlighted that she was a pupil of Leschetizky. One day I remember Walter [Rogers] asking her what he was like as a teacher. She said, “I don’t really know. I only had two lessons with him!”

One of the most interesting of Brunswick artists was Marion Harris, who seems to have influenced not only Rudy Vallée but many other performers. How did you get her to record for Brunswick?

Marion was our biggest-selling female artist in our popular-music division, and she was ahead of ones like Ruth Etting, Belle Baker, and Kate Smith when they were starting out. Marion had been a headliner in vaudeville so she was very much in demand, and she had made some recordings for Columbia [7] before we got her to come to Brunswick.

.

Marion Harris and Isham Jones’ Orchestra (Jones second from left)

(G. G. Bain Collection, Library of Congress)

.

The first recordings I remember making with Marion was when we put her with Isham Jones’s band. Her voice came through spectacularly—I was going to say “loud and clear”—on all of the acoustic records she made with us. Hers was one of those voices like [Mario] Chamlee’s, which the old [acoustical] process captured wonderfully. She was always available whenever we wanted her, and we recorded more songs with her than probably any other female pop singer in our catalog.

Brunswick also had Margaret Young, who sang some of the same blues songs as Marion Harris. What do you recall of her?

There was nothing original about Margaret Young. She had been in vaudeville, and then she patterned herself after Marion Harris. But [Young] wasn’t in the same league as Marion—not by a long shot. For every Margaret Young record, we probably sold twenty times as many Marion Harris records during the acoustical days. When we went into radio with our “Brunswick Hour” broadcasts, we made sure Marion was on as many of those [broadcasts] as possible. Really, Marion was the first white woman to sing jazz and blues the way the great Negro singers sang them.

.

Margaret Young (G. G. Bain Collection, Library of Congress)

.

That brings me to the topic of what were called “race records” in the 1920s. Did Brunswick have a separate catalog of these “race records”?

Yes, although we limited it mostly to the Vocalion label. Vocalion was a low-priced label that we thought would be attractive to Negro buyers. [8] Now, we did have a very fine black singer, Edna Hicks, and some other blues singers whose names I’m sorry that I don’t remember. We had several different catalogs, just like Victor did. One of them was a “Jewish catalog” that featured singers like Isa Kremer, who sang Yiddish folk songs, and several great cantors as well. Like Victor and Columbia, we also had catalogs in other languages, which were distributed in Europe, South America and Asia.

.

Although Brunswick had a race-record program, its Vocalion label served as the company’s primary outlet for race material. Originally managed by Jack Kapp, the race department was taken over by Mayo Williams in 1928, after Kapp was promoted to general manager.

.

The Vocalion label also included what today would be called “country and western,” correct?

Yes, although it was called “hillbilly music” back then. Jack Kapp was the manager of Vocalion after we acquired the label.

Jack Kapp, who founded the American Decca label?

Yes, that Jack Kapp—and I apologized to him so many times for the way I dealt with him at Brunswick that he finally told me to stop it! I couldn’t stand anything “hillbilly,” but Jack would scour the hills of Kentucky and West Virginia for these backwoods yodelers and fiddlers, and he would record them wherever he could come up with a makeshift recording studio.

I had to meet with Jack quarterly, sometimes more frequently, so he could play these field recordings to get my approval for them. He knew that I hated that kind of music, but he was always trying to “convert” me. He’d be playing a test pressing and he’d say to me, “Now, isn’t that a good guitar lick? And how about that harmonica!” I’d roll my eyes and tell him, “What you call a ‘good guitar lick’ is what I call bad guitar playing!”

We’d go ’round and ’round arguing about these hillbilly players, and I always ended up approving whatever he brought. The reason I did was because, first, they sold a lot of records in rural areas that never bought Brunswick records until then, and second because Jack kept finding better and better talent. Plus, Jack was so enthusiastic about discovering new talent that his enthusiasm rubbed off on me and everyone else he worked with.

Were you surprised at how successful he made Decca?

Honestly, when he pitched the Decca idea to me and invited me to invest in it, I said no because I didn’t think there was a market for phonograph records anymore. There had been all kinds of improvements in the technology, of course, but I was so involved in radio that I didn’t pay any attention to phonograph records. I had put all of that in the rear-view mirror when I left Brunswick, and when I heard that Jack had been named manager of Brunswick after the 1929 stock-market crash, I felt sorry for him. But what I should have considered was how determined, how driven, Jack was.

.

.

Jack Kapp (right) during his Decca years, with former Brunswick stars Al Jolson and Bing Crosby

.

These days, we hear a lot about “visionaries.” Jack Kapp was a real visionary. His success with Decca kept the recording industry going, and his investors—especially Bing Crosby—believed in him and put a lot of money into Decca. A lot of the artists Jack had worked with at Brunswick followed him to Decca. Just when Decca was doing very well, there was a shortage of shellac that Jack had to contend with. That happened when we [the U.S.] entered World War Two. But he weathered the shellac shortage, and Decca grew during the war.

Then came the revolution in the industry when Columbia brought out the long-playing record, RCA came out with the 45 r.p.m. format, and magnetic tape revolutionized how recordings were made. It was Jack Kapp, in my opinion, who kept the industry going during the middle of the Depression. Without him, I’m not sure that there would have been much of an industry left because the vast majority of Americans barely had enough money to buy food.

Earlier, when you were speaking about Marion Harris, you mentioned two topics that I want to ask you about: electrical recording and the “Brunswick Hour.” Frank Black was played an important role in the “Brunswick Hour,” if I’m correct. How did you and Frank Black meet?

Walter [Rogers] and I hired Frank as a staff pianist and an arranger for our classical and popular recordings at Brunswick. I’m not sure when we hired him, but I would guess 1921 or 1922, after we were well-established in the industry. Frank was the fastest and most versatile arranger I’ve ever known, and I’ve known and worked with a lot of them. As you said, he had an important role in the “Brunswick Hour” broadcasts. He wrote many of the arrangements for them and was the pianist in them too.

.

Frank Black (undated photo, and a 1937 caricature)

.

How would you compare the two of you as pianists?

Frank was the better pianist—he was much more versatile than I was. I played in one style, which we called “ragtime” back then, but [which] came to be known as “stride” when James P. Johnson and other black pianists became well known. That was the style I learned in St. Louis, the style that Scott Joplin helped me to refine. Frank, on the other hand, could play in almost any style, and he could hold his own with some of the classical pianists. But his most important role for us at Brunswick was his extraordinary speed and output of very imaginative arrangements.

What led you to become a partner of his in radio, where the two of you became nationally known as a team?

That started with the first broadcast we did of “The Brunswick Hour.” Between us, Frank and I wrote all the arrangements for that first broadcast. We just clicked when it came to writing arrangements for radio broadcasts.

Those “Brunswick Hour” broadcasts were well-received by the critics, and certainly by the public. Was that your first performance on radio?

Yes. Before that, my only experience with radio was building them for me and my family and friends. [David] Sarnoff envisioned radio becoming the dominant form of entertainment, and between 1920 and about 1924 radio technology improved to the degree that the [radio] sets had cone-type loudspeakers that made it possible for a whole family to listen to a broadcast. Until then, loudspeakers that were used with one- or two-tube receivers were basically megaphones connected to a diaphragm like the one in a telephone receiver.

.

The earliest “Brunswick Hour” programs featured a “Music Memory Contest” that was suspended after several broadcasts. (March 1925)

.

Do you remember how you felt about hearing radio broadcasts through an electrical amplifier and loudspeaker, compared to listening to an acoustical phonograph record?

Well, hearing the full range of sound coming through a cone-type loudspeaker made what we were doing in our recording studios seem almost primitive by comparison. It was obvious that radio was going to replace phonographs as the source of entertainment.

When you look back, you can see why radio was the future. Our twelve-inch phonograph records had a playing time of about four minutes at the most. A radio program could be any length, from fifteen minutes to an hour or more, and it was free in those days. Later, when sponsors came in [to fund radio broadcasts] and network programs aired commercials at the beginning and end of a [radio] show, radio was still free of charge to the people at home.

Do you recall the financial recession of 1921–1922 and its effects on the recording industry?

Oh, yes. Phonograph sales went to hell, and so did record sales. Like Victor, Brunswick weathered that downturn better than the other smaller companies. In our case, it was because of the parent company’s diversity and the money they could afford to lose in the phonograph division. But I would say that by 1923, anyone in the recording industry could see what was going to happen [with radio] because acoustical recordings cost money and their sound was inferior compared to a high-quality radio broadcast in the middle-1920s.

.

©2019 by James A. Drake. All rights are reserved.

_______________

Editor’s Notes (Added with interviewer’s approval)

[1] The Valentino session (May 14, 1923) preceded Chaplin’s by two years.

[2] Brunswick catalog number 3299 was finally assigned to the recordings in 1926, but the release was cancelled. Both selections were remastered by Brunswick in August 1930, with the addition of a spoken introduction, for the apparently unrelated Celebrities Recording Company (Los Angeles).

[3] Hardy, Navarro, and Boles made no known recordings for Brunswick.

[4] This recording, made for Edison on November 18, 1924 (one month before Munn’s first Brunswick session), was eventually approved for release in October 1926.

[5] However, Munn’s earliest Brunswick recordings are acoustic.

[6] Trumbauer was added beginning with a session on March 13, 1924, Lang beginning with a session on December 10, 1924. Jugs were not used.

[7] And Victor.

[8] Vocalion records initially were reduced to 50¢ from 75¢ following the label’s acquisition by Brunswick, but were soon reinstated as a standard 75¢ line following dealer protests. However, Haenschen is correct in observing that Vocalion served as Brunswick’s primary race-record outlet. Jack Kapp was in charge of the race catalog, which probably explains Haenschen’s limited recollections.

Discover more from American Sound-Recording History from Mainspring Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.